Just Like Family: FDNY embrace kin of the fallen

Elizabeth Moore

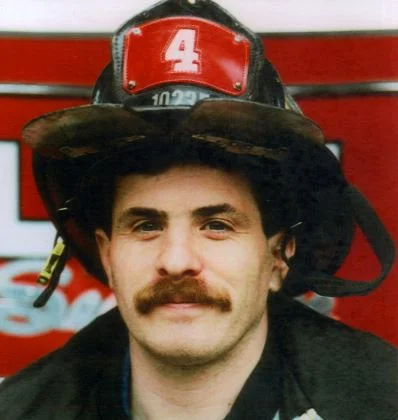

By Saturday, Keith Kern had called the florist to order a big Maltese cross in red carnations with Joseph Angelini Jr.'s fire department badge number in the middle. He had arranged for a helicopter fly-by, a motorcycle escort and a place for the family and friends to eat after the memorial service.

That afternoon, Joey Angelini's wife, Donna, called: She had finally told the kids their father had been killed in the collapse of the World Trade Center, and they were not taking it well.

Kern, a firefighter with Manhattan's Ladder Co. 4, had been taken off the company schedule and assigned full time to helping four of the firehouse's 15 bereaved families through the mourning period, and Donna needed him now. Soon after he settled onto the Angelini's living room sofa in Lindenhurst on the evening of Oct. 13, he found himself eye to eye with 7-year-old Jennifer, in one of her father's old fire department T-shirts, tears on her cheeks.

"Why isn't my daddy coming home?"

Kern exhaled. His firehouse hadn't lost a firefighter in 30 years. He is no psychologist, and he had tried to turn this duty down. But he has been married for 25 years, has five kids and two grandkids, and he will never forget Joey Angelini.

"We need to talk," he told the child. Jennifer took him by the hand and led him into the master bedroom, and they climbed up onto his old friend's bed for a heart to heart.

"There was - an accident," he began, gingerly sorting through this phrase, that word, as Jennifer stared into the darkness.

When she was finally asleep, he went back to the living room sofa, where Donna Angelini, turned to him with tears in her eyes.

"Why isn't my Joey coming home?"

By policy and by passionately held tradition, New York City firefighters embrace the families of their lost as if they were their own blood kin. Since Sept. 11, when more of its men died in one morning than had in the past 50 years, New York City has pulled firefighters out of every company that lost someone to provide full- time support to the wives, mothers and children of those lost in the trade center attacks.

The survivors, about 250 widows and 600 children, know they can expect to be well provided for, financially: They receive their husband's full salary, tax free, for life or until remarriage. The union provides stipends for the children. And millions of dollars in donations are flowing in from around the world. But what the firefighters do is about something more than money.

Does the widow need someone to mow her lawn? Consider it done. Kid needs a ride to the orthodontist, or expert help with his fastball? Handled. Is she lonely tonight? A couple of the guys and their wives have put together a dinner party on three hours notice and insist that she come - and don't worry about a sitter, that's taken care of.

"I just got myself 22 new husbands," Donna Hickey said Sept. 17, looking around the Rescue Co. 4 firehouse in Queens at a roomful of men who had worked, played, eaten and bunked with her husband, Capt. Brian Hickey, for so many years and were now fussing over her.

Aiding 343 families at one time has put a tremendous strain on the departmental bureaucracy, but firefighters seem, if anything, even more stubbornly determined to protect and nurture their own, and to claim the wives and children of the lost as permanent family.

Rescue Co. 3 firefighter Ray Meisenheimer's wife Joanne didn't need to worry about how she was going to manage the kids and the memorial service and finish construction of the dream home the couple was building out east: Meisenheimer's lieutenant, captain, and other firefighter friends have made regular trips to meet with the contractor on site since he died, and Rescue 3 firefighters plan to move her into the new house next month. Rescue Co. 2 firefighter Eddie Rall's wife, Darlene, only had to murmur about how much her boys loved the Mets before his buddy Bob Galione was on the phone to the team's front office lining up a red-carpet visit that included a meeting with the entire team and its manager. The wives know they have to be careful what they say, the men outdo each other in their efforts to please them.

"It's an unspoken rule, our first commandment: loyalty to our family, the brotherhood, every firefighter," explained Vincent Geloso, an Engine Co. 10 firefighter who is one of two men assigned to help five bereaved families in his firehouse on Liberty Street across from the trade center ruins. Geloso is bird-dogging benefits paperwork and funeral arrangements and rides to funerals for the families he helps. But he also lined up some firefighters who donated their construction skills to rebuild a stairway in Paul Pansini's house. And he has decided to repair a boat that sits up on blocks in Jeffrey Olsen's backyard in Staten Island. He wants to take Denise Olsen and her children out on the water in it next year.

"We're friends forever now, and that's just how it is," Geloso said.

At Christmas, there will be gifts for their lost friends' children, not just generic, charity-type presents but substantial ones, the kinds their fathers would have picked out. Birthdays will be remembered for years to come. And there will be fresh memorial wreaths placed on the graves year after year.

"Unless you have been in it, you could never understand how deep it goes, how caring these people are," said Phyllis Valentino, mother of Louis Valentino, a Rescue 2 firefighter who died in 1996. That caring seems only to beget more of the same.

Valentino and her daughter-in-law, Diane, attended the wake and funeral last month for Rescue 2 Firefighter Billy Lake, and she has gone down to that Crown Heights firehouse this fall to try and cheer up the men, who lost seven from their house in the collapse.

When Valentino died, she recalled, Billy Lake was the one who showed up at her house in Bensonhurst with hot bagels and cream cheese. His captain, Ray Downey, sat at Phyllis Valentino's dining room table to plan the funeral. After he learned she'd prayed the rosary every morning for 30 years, Downey and his wife Rosalie, also devout Catholics, brought back a statue of the Blessed Mother for her from a trip to Fatima. Department Chaplain Mychal Judge, overnight became Phyllis' spiritual adviser. Whenever he was coming through the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel after that, even if it was 11:30 on Christmas Eve, Judge would stop by to say hello.

"We had him over for dinner many times," said Phyllis Valentino, who has come to feel like everybody's mom down at Rescue 2. "I only got to know them really since that happened. They adopt everybody."

In normal tragedies, when firefighters died one or two at a time, and funerals drew 10,000 people, the barrage of attention made some women positively claustrophobic, and they had to put out word to the men to back off so they could sort out their grief in peace. There has been little danger of that since this disaster, which claimed Judge and Downey along with the rest.

No one has noticed the strain more than Denise Ford, widow of Rescue Co. 4 firefighter Harry Ford, who was one of three firefighters killed in an explosion at an Astoria hardware store on Father's Day. She and the other Astoria widows have been in constant motion since Sept. 11, sipping coffee and eating lunch, and holding hands with as many of the hundreds of new department widows as they can, partly because the department is so clearly overwhelmed.

Ford learned how a city firehouse handles a death after two other firefighters from Rescue 4 died in 1992 and 1995. Harry Ford left home and joined his entire company to their Woodside firehouse, where they spent the next several days eating, sleeping, and drinking together day and night, and preparing the funerals with the widows.

"You willingly give your husband up to something like this because it's important, and it should be done," she said.

From the day she found herself at Elmhurst Hospital receiving the news from the department doctor that Harry was dead, Ford learned a fire department widow is never alone: Rescue 4 men carried her through the mourning process step by step, making the arrangements, finding dinner for the family, driving her, protecting her, she said, as if they were her own brothers. Company members knew sports had been important to Harry, so they started taking their two sons to Jets practice at Hofstra and other events. They knew Harry had been planning to renovate his downstairs and redo his roof, so a bunch of them were going to come down and do the work themselves. Then Sept. 11 arrived, and her phone rang.

The company had just lost six men at the Twin Towers, and they were trying to help the wives, in between round-the-clock shifts searching the site for the lost. The office that normally counsels widows on benefits was just too busy, and did she remember how the system worked? There hasn't been a slow day since.

"What happens with us, the kindness of so many people who came, sent letters, did things, you become humbled through your husband's death and you feel, as you receive, so shall you give," Denise Ford said. "Even though it was very fresh with us, you sort of felt compelled, that you needed to do this."

Since Sept. 11, the men have been apologizing profusely about having to put off Denise Ford's renovation and hassling her for the boys' football schedules so they can go to the games. They're taking the boys skiing this winter, too.

"I was told when this is over I better make sure and call them and they have to help me with something, otherwise they are going to be very angry with me," she said. "It's important to them that I am still connected to them. And I will ask them for help, because it will make them feel better."

Donna Angelini readily admits she still needs the help for her own sake. She knows she is Kern's toughest case. Not only have her children lost their father, but their grandfather, Rescue Co. 1 firefighter Joseph Sr., also died that day.

That first week, once she got the kids off to school she was unable to do much of anything as she waited for word about Joey. She sat home, unbathed in her pajamas, numbly watching the laundry climb up the bedroom wall, food remains congealing on plates here and there, and tear-stained tissues overflowing from the bathroom wastebasket.

When Kern started coming to her house around the end of September, he noticed a pile of unpaid bills and paychecks that hadn't been deposited. Joey always handled those, filing and organizing everything and logging it all on their home computer. Morning, noon, and night, Kern prodded Donna to eat, to let him take her to the grocery store, to the bank, to apply for benefits, to fix the rotting pipes that had caved in the shower wall, even though Joey would not approve of the way the plumber planned to do the job.

"I'm still thinking: 'Joey,'" she said.

Jennifer, meanwhile, had begun taking shelter each day in the principal's office, because she couldn't stand hearing kids say her dad was dead. Jacqueline, 5, seemed to find a way to be out of the house with relatives and friends almost all of the time. Three-year- old Joseph III just cried for his father.

Kern brought a Technodog for the boy, and a Tonka payloader. For the girls he brought a Starlight Fairy Barbie and a Bedtime Baby Chrissie. He got down on the floor and played with them, rough- housed, took them to the safe-Halloween party at the school. Donna kept talking about her husband. He rubbed her shoulder as she wept, told her to just let it out.

As weeks passed, and Joey Angelini's eggplants swelled untended under a blanket of autumn leaves in his garden, and his tomatoes grew fat and red and finally shriveled untouched in the waning light, Donna Angelini still would not file for a death certificate. She could not bring herself to clean out his firehouse locker, plastered with photos of their wedding, the births of their children, the kids growing up. She left his ChapStick untouched on the locker shelf. Joey would be angry if he came home and found that people had been messing with his stuff, she said.

She hasn't washed the pillowcase he used before he left, and she sleeps in the undershirt he took off before heading into his last shift in the city, clutching a framed 8-by-10 photo of her husband. She gets upset if people touch these things.

And when the department took the widows to the site for a service and tour Nov. 2, it didn't help at all. Donna saw baker's racks in a basement area of the tradecenter that were untouched. She's heard that at the bottom of Tower One there were perfume bottles still standing. What if they find all these guys, and they're intact, and they're fine, but they've starved to death? She also has this theory that keeps running through her head, which she calls "insane," that the reason they're not finding the men of Ladder Co. 4 is because Osama bin Laden has them all held hostage somewhere.

"I just keep waiting for them to call and say, 'We found him, he's really, really bad, but we got him,' and I'm going to try to take care of him," Angelini said. She finds it hard to breathe.

"I'm in big-time denial," she admitted.

Kern has listened to all this, but he keeps pushing her to face the truth. Sometimes he has had to make her cry, he has been so insistent, "otherwise, she'll be forever waiting for him to come through that door."

Valerie Kern has seen the strain this has put on her husband. It started in the frenetic first days after the attack, when he poured himself into digging and searching in the smoking pile, but kept having to return empty-handed to the anxious faces of his lost friends' wives waiting at the firehouse. At home, he'd sit in his chair and just stare. Now, it's the hand-holding. Keith Kern is not a talker, but he wants to help people, and this terrible thing can't be helped.

"He feels like he has to do it, he wants to do it, and he knows how I would be if it were the other way around, but he's tired," Valerie Kern said. " ... When he comes home, he just wants to be hugged all the time."

When the funerals are finally all finished, she worries that he will be hit worse than ever by the reality of what happened.

But Keith Kern can't think that far ahead. He doesn't know when the department will terminate his special duty, but he doesn't think it really matters.

"This will never be over for me," he said. "I will not forget."