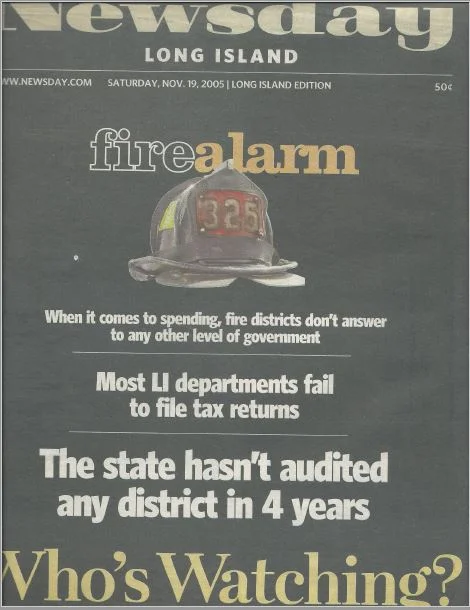

Fire Alarm Series Day 7: The Oversight

By Elizabeth Moore

November 19, 2005 11:59 AM

The treasurer of the Bayville Fire Department managed to steal $209,000 over three years without anyone noticing because he didn't let the department's accountant see the books, and no one else asked.

Volunteer leaders stymied, then weakened, a Suffolk County bill to track and report how long patients must wait for an ambulance despite a plea from a legislator whose brother-in-law died while waiting for help.

And no state, county or town agency collects facts as basic as who the volunteers are, how many people they protect, or how fast they get to fires.

Over the past 50 years, Long Island's network of small-town volunteer fire departments has evolved into a vast enterprise, yet four out of five fire agencies here answer to no higher level of government about the way they spend money or deliver lifesaving services.

Long Island volunteers preside over $1 billion in buildings and equipment, cost more than $319 million a year, administer 120 pension funds and protect 2.7-million citizens. Yet the state comptroller hasn't audited a Long Island fire district since 2001, and how volunteer departments raise and spend donations from the public is exempt from the supervision most other not-for-profit groups receive from the state attorney general.

The counties have little say in coordinating the operations of local departments, even in areas where county charters specifically direct them to play a role.

Fire departments routinely fail to file charitable tax returns on the donations they receive, and only about half of the departments or their benevolent associations turned in required annual reports in 2003 to the state showing how they spent about $10 million in state insurance surcharges.

And politicians have shown little inclination to take on the respected, well-organized and civically active volunteers, usually deferring to fire commissioners chosen in elections that draw sparse participation beyond volunteers and their families.

"I don't think our system is working," said Robert Kreitzman, a former commissioner in Selden, who says he has asked in vain for the state to audit his own district. "They don't come in to check anything ... and there's issues that would curl your hair."

Most of the laws governing Long Island's fire agencies were written in the 1930s, when New York's local governments were taking their modern form, and revised in the 1950s, when the explosion of suburban populations created an urgent need to make sure volunteer firefighters had enough tax revenue to buy water, trucks and buildings.

"Practices that perhaps were accepted everywhere as recently as 20 years ago are no longer acceptable today because society has changed," said Bayville Mayor Victoria Siegel.

"The expectations of society have changed. There's more money involved."

Fire spending receives varying degrees of scrutiny. The 124 fire districts, which cost on average $124 per resident, have their budgets approved by relatively obscure boards of elected commissioners.

The 21 independent incorporated fire companies, which cost about the same, bill towns and villages for their services with little input from local officials. The 33 village and city departments, which cost about half as much per resident, have budgets controlled by higher-profile municipal governments.

The only meaningful outside financial scrutiny of fire districts comes in audits by the state comptroller. That agency audited eight of New York's 867 fire districts in the past two years, but it has audited none on Long Island since 2001, and just 22 here in the past 10 years.

"Many of our resources have been allocated to looking into school finances following the recent financial problems in several districts," explained Jennifer Freeman, a spokeswoman for state Comptroller Alan Hevesi.

Another spokesman added that the office gives regular financial training to local officials and has prepared special reports on topics such as volunteer pension programs and financial controls, but not focused on specific districts.

"The whole system is lax, that's my impression," said former Cold Spring Harbor fire Commissioner Henry Kieronski. He said he "tried to get the comptroller's office to conduct an audit; they said, 'We don't have the people.'"

State law requires districts to file annual financial reports with the comptroller and town clerks, but they don't have to have the reports audited for accuracy.

The comptroller's office does not have the authority to audit the independent incorporated fire companies, such as Bayville.

Nor does it review the donations that fire departments raise from the public. Citizens may find it hard to learn how much their fire department raised or how it spent the money, even though they are entitled to that information. Under federal law, departments that take in more than $25,000 a year are required to file charitable returns with the Internal Revenue Service and to provide them to the public upon request.

About one in five of all departments have filed, records show. The returns that are filed show that departments can amass significant wealth.

Through 2004, the Montauk Fire Department had accumulated more than $1.3 million in cash and assets, while Smithtown's department had $805,459 by 2003, the most recent IRS records available show.

"A lot of good-intentioned people in the volunteer fire service just have no idea that they are supposed to take care of this," said Ed Cooke, legal counsel to the Firemen's Association of the State of New York, the volunteer lobbying group.

"You don't see accountants and lawyers running fire departments, on the whole, and it's probably good that you don't."

Lacking fiscal precautions

Weak financial controls at fire districts have allowed abuses throughout the state, a 1999 report by the comptroller's office noted. After problems showed up in audits from Long Island to Buffalo, the state found that fire districts weren't taking basic financial precautions, such as having someone other than the treasurer receive bank statements and canceled checks.

Though Bayville is not a fire district, it was the absence of those same controls that allowed treasurer Salvatore Lombardo to steal $208,850 from January 2000 to June 2003.

"They said to me that they operated on trust in that volunteer firemen are a brotherhood and they all know one another," Siegel, the Bayville mayor, said. "They trust one another, and that's what makes them effective."

Lombardo paid back the money and later pleaded guilty in April to third-degree larceny.

Similar lapses have been blamed for many of the other firehouse corruption cases on Long Island. Over the last decade, criminal cases have been brought in Great Neck, Centereach, Franklin Square, Syosset, Dix Hills and, most notably, Lakeland.

A 1997 Suffolk County grand jury identified a lack of financial experience as a key reason a spending scandal developed in Suffolk's Lakeland Fire District in the mid-1990s.

After a 1995 state comptroller's audit found more than $400,000 in illegal no-bid contracts and questionable travel advances, the grand jury probed further and discovered Lakeland fire officials had committed perjury and accepted bribes, kickbacks and extravagant "Christmas presents" from contractors.

No commissioner had any training in fire administration or received any once elected, the grand jury found. Then-District Attorney James M. Catterson Jr. forwarded several of the grand jury's financial reform recommendations to Albany, but state lawmakers never acted on them.

"Here I am, somebody with no sort of education in any sort of finance who gets to play with $2 million," said former Lakeland Commissioner Robert Galione, who testified before the grand jury and persuaded his board to have its books audited annually by a private firm. "If you want to keep yourself out of trouble, go find somebody who knows what they're doing."

Similarly, a 1999 comptroller's study of firefighter pensions questioned whether volunteer officials had the financial skills to manage them.

Lots of leeway

Beyond finances, fire agencies have wide latitude to set their own policies and performance standards.

While volunteers bemoan mandates from the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration that have increased training and required ever-more sophisticated equipment, they still get to decide who can join, how they'll fight fires, how they'll work with other departments and what response times are acceptable.

State law leaves it to volunteer officials to determine who qualifies as an active firefighter, a designation that entitles them to a variety of state and local benefits and tax cuts.

In Rockville Centre, for example, 130 of the 349 people listed on the department roster in 2003 answered fewer than 20 alarms each that year, records show. Twenty-eight of them answered none at all. The roster also included at least one 85-year-old man living in Florida.

"There's a lot more to a fire department than answering fire calls," said Chief Peter Grandazza. " ... Just because someone reaches the age of 65 ... should we throw them out of the firehouse?"

A bill to define what constitutes "active" and to establish a state registry of firefighters failed in the state Assembly, but homeland security concerns have revived the issue, said Edward Carpenter, president of the firemen's association.

"Unfortunately, no actual number exists anywhere in the annals of government ... as to the true number of volunteer firefighters and EMS personnel across New York State," Carpenter said. He said his board is discussing a proposal to count the active volunteers, issue them identification cards and inventory their various skills.

State law authorizes county fire officials to "coordinate" fire services, and in some upstate regions, this adds up to real clout. But on Long Island, both counties have left most fire policy to the volunteers.

In Nassau, there is no policy role for anyone but a volunteer. Without any input from the county executive or the legislature, the all-volunteer fire commission appoints the fire marshal and every employee on his $12-million payroll, including the fire dispatchers.

This leaves the only arm of county government that deals with fire protection focused on volunteers' needs. For example, the county dispatch center does not collect, summarize or analyze fire and ambulance response time data that might help residents and fire agencies evaluate emergency performance.

"We're not concerned about how long it takes to get these guys there ... Our primary job is to make sure responders don't get hurt or killed," said Peter Meade, an assistant Nassau fire marshal. "... What they do when they get there, that's their business."

In Suffolk, the county executive appoints the director of fire, rescue and emergency services, and the all-volunteer commission's role is limited to recommending candidates for the job.

Historically, though, both the county executive and the director have deferred to the volunteers. This year, County Executive Steve Levy chose a candidate, Joe Williams, who was not recommended by the volunteers but was popular with them.

One of the first things he did was to launch the county's long-planned computer-aided dispatch system, which is expected to speed emergency response.

Another thing Williams did was stop distributing the closest thing to a report card that either county issued on fire and emergency medical services: a comparison of ambulance response times. He felt the report was flawed because it lacked consistent information for all the departments.

"I felt that people were looking at this report and judging the departments, and all the factual information was not there," he said.

He said the county would provide individual departments with information about their own performance if they request it.

Protecting their turf

Volunteers continue to fiercely guard their independence, and their influence can be seen in how gingerly the counties and their commissions deal with emergency service issues.

Even when the county charters direct officials to work out specific issues among departments, they haven't.

Nassau's charter instructs its fire commission to "recommend the standardization of equipment, such as hose couplings and threads." It hasn't gotten that done in more than 67 years.

Elmont fire hydrants only accept one type of fire hose, while Roosevelt hydrants need a different one and Garden City hydrants a third. So departments must carry a variety of special hose adapters to help at neighbors' fires. Some have taken to color-coding their equipment to ease the confusion.

Suffolk's charter says the fire, rescue and emergency services director should "establish and supervise programs for mutual aid." While departments have informal "mutual aid" arrangements with their neighbors to cover for each other and respond to large emergencies together, the county has no comprehensive policy on how to get help to people faster.

"It's their prerogative," Williams said of the local chiefs who under state law are in command at fires. "It's how they want to do it."

Formal policies could allow county dispatchers to automatically send other departments who have a crew on the road or may be nearer to the emergency, saving valuable minutes.

For their part, volunteers say a countywide, one-size-fits-all approach to emergency services would be a disaster. Only the volunteers have the insights needed to match local resources to neighborhood needs, they say, and offer the sensitivity that only neighbors can.

"I happen to know what Lladros and Hummels are, and as an officer and fire chief, I'd tell our guys, 'Hey, be careful of that cabinet,' just moving it easily so we can get to the fire behind the wall," said Michael Chiaramonte, a former Lynbrook chief and a national speaker on volunteer retention.

"I remember going into a temple and going to get the Torahs out. We took the Torahs out first ... It's kind of that intangible, take-care-of-our-neighbor kind of attitude which I don't know if you could put a dollar figure on."

State law places authority over protection at the most local level. This home rule puts the power to run fire districts, which administer the vast majority of fire protection on Long Island, in the hand of boards of commissioners who answer to no higher level of government. Fire district elections receive little notice from the public or the media.

A Newsday analysis of dozens of elections since the late 1990s found scant turnout and votes dominated by firefighters, whether the issue was a new commissioner or millions in new taxation.

For example, when Dix Hills put a $4.4-million firehouse bond to a vote in 1998, a mere 94 of the district's roughly 17,000 voters showed up, and at least 80 of them were members of firefighter or district employee households.

Low turnout

It was a recurring trend in other elections: In Patchogue in 2001, a $500,000 bond issue had about 3 percent turnout, more than half from fire households; in Manhasset in 2002, for a $4.9-million bond, there was less than one percent turnout, three-quarters from fire households.

Even a hotly contested election Thursday on whether the Setauket Fire District should borrow $17.5 million to build a new firehouse drew only 2 percent turnout. The bond issue, which some firefighters had opposed, failed 444 to 25.

Volunteers have been able to maintain their independence because politicians have been wary of interfering with such trusted and influential citizens.

"They are an active component of every community," Suffolk Deputy County Executive Paul Sabatino explained in an interview before taking office. "They have extended families and social contacts and can mobilize and organize people on a moment's notice. On things they care about, they are too active and too large to be ignored."

Here, veteran political operatives say both parties pay close attention to firefighters.

Last month, just before his re-election, Nassau County Executive Tom Suozzi mailed out an "important message to firefighters and ambulance workers" thanking them for their service and recounting his efforts on their behalf, including an agreement to build a new $50-million communications center, the addition of police ambulances and the approval of $1.3 million for a firefighter museum.

"The timing was related to the capital budget process," Suozzi said of the mailing.

As a Suffolk legislator, County Executive Levy initiated a horn-honking rally of angry volunteers outside the county government building in 1989, where both volunteers and officials denounced a Newsday series calling attention to problems with ambulance service.

In 2003, as a state assemblyman, Levy sponsored at least six property-tax-cut bills for volunteers and was lead sponsor of the one that eventually passed, which provides a 10 percent exemption.

"There's a great deal of pride and dedication that comes with the volunteer force," Levy said earlier this month, "and it has worked well for us for decade after decade."

Few have risked taking on firefighters on any issue.

Nassau County officials learned that lesson 13 years ago when they cut the Nassau fire academy budget during one of its many fiscal crises.

A parade of fire trucks and angry volunteers chanted "Joe's gotta go," directing their anger at then-Hempstead Presiding Supervisor Joseph Mondello. The cuts were restored.

Some officials are shocked by the treatment they get. Joseph Caracappa, then the deputy presiding officer of the Suffolk Legislature, told lawmakers in November 2003 that he'd gotten calls and e-mails, even from the county's own appointed commission, "almost to the point of a threatening nature" after a county report criticized spotty ambulance response.

"I received calls ... 'How dare this legislature ... Who are you? You failed the fire service,'" he said.

But eventually, the report led to the first serious bill in more than a decade to improve accountability for ambulance response times -- sponsored by three lawmakers who were about to leave office anyway. Volunteer leaders turned out in force and killed it in committee last fall, saying it would only increase bureaucracy.

But lawmakers say they find it hard to continue opposing measures that might help save lives. This spring, they passed a watered-down version that replaced penalties with incentives for cooperation.

"I understand the volunteers, sometimes they get focused on 'We volunteer a lot of our time and don't criticize us,'" said Legis. William Lindsay (D-Holbrook), who told lawmakers that his brother-in-law died while waiting for a fire department ambulance in 2002.

"It really isn't meant to be a criticism; it's meant to improve the system. The county is now up to 1.4 million people. I'm not advocating that we go to a paid service, but we have to be more efficient.

"You're talking about a lot of lives we're protecting now."